Performing Inertial Odometry Using LSTMs - Calculating the Compression Depth and Rate During CPR Using Accelerometer Data

2024-12-07

I wanted to discuss a project I worked on, which I presented at the International Science and Engineering Fair. I made a portable device for helping bystanders perform CPR with a higher accuracy, named Rebeat.

One core functionality was the real-time tracking of compression depth. Theoretically, it should've been pretty simple. Consider the problem of double integration. Given the acceleration of a certain moving object, we can compute the displacement by integrating the acceleration twice. It's one of the most basic problems you encounter in high school physics. But is it practical in real life?

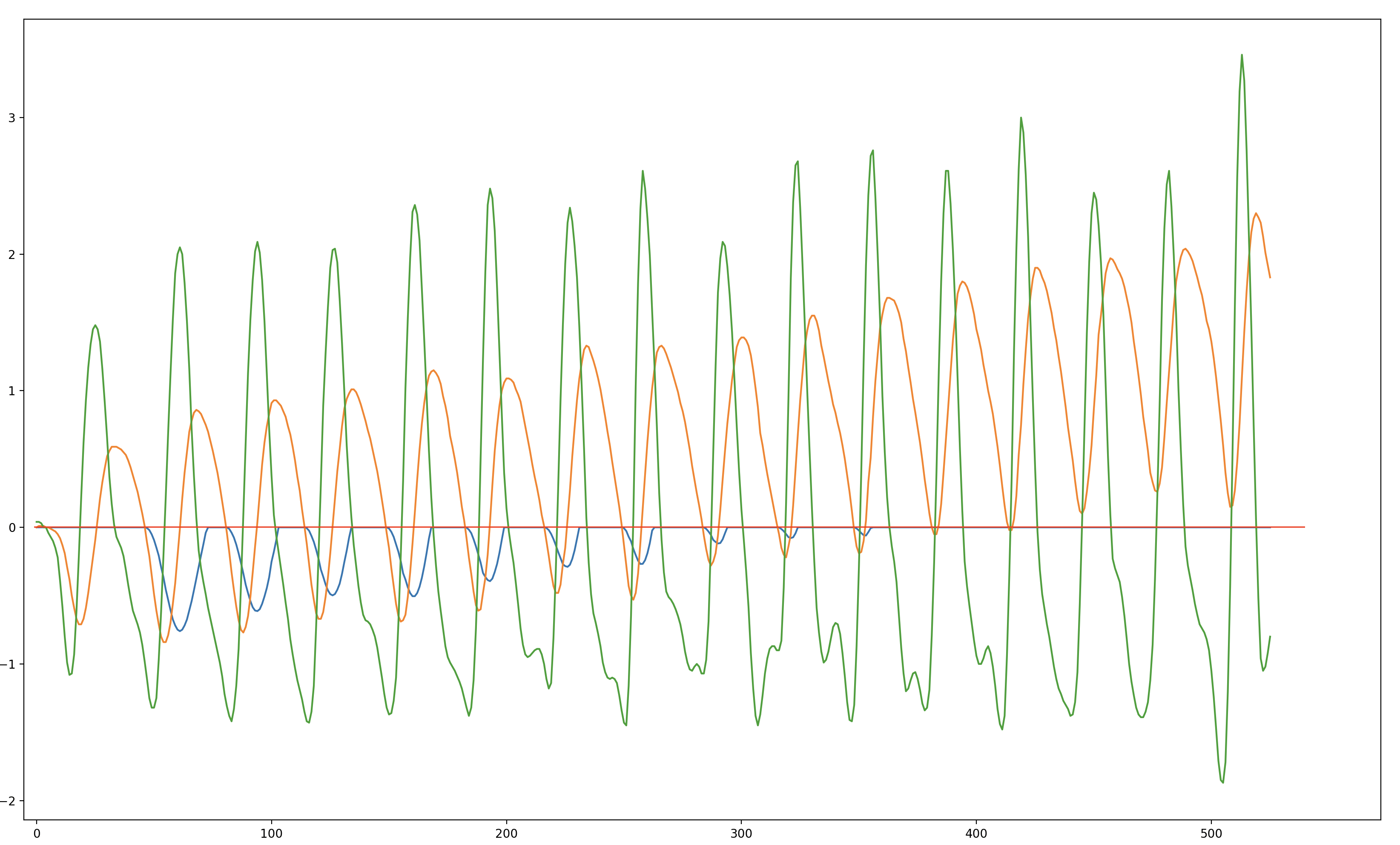

It turns out, no. Specifically, I'm talking about the case where you have to use noisy data from accelerometers. Sensors usually have something called "Gaussian White Noise," which is a type of noise that's normally distributed. Naive double integration ends up accumulating a lot of that noise, resulting in calculations that wildly differ from the actual value in just a few seconds' time. Not so ideal.

There are a few techniques to get rid of that noise however. First of all, you can use a high pass filter to remove any signals that might occur even when the accelerometer is stationary. Then, you can use a moving average filter to remove the gaussian white noise. This is all covered in NXP Semiconductor's Implementing Position Algorithms Using Accelerometers.

But in my own project on CPR compression depth and rate calculation, I found that the improved method still went haywire if I didn't reset the values every now and then. After a bit of digging, I found a research paper on deep learning methods for inertial odometry, a fancy word for the exact same problem discussed above. Here it is.

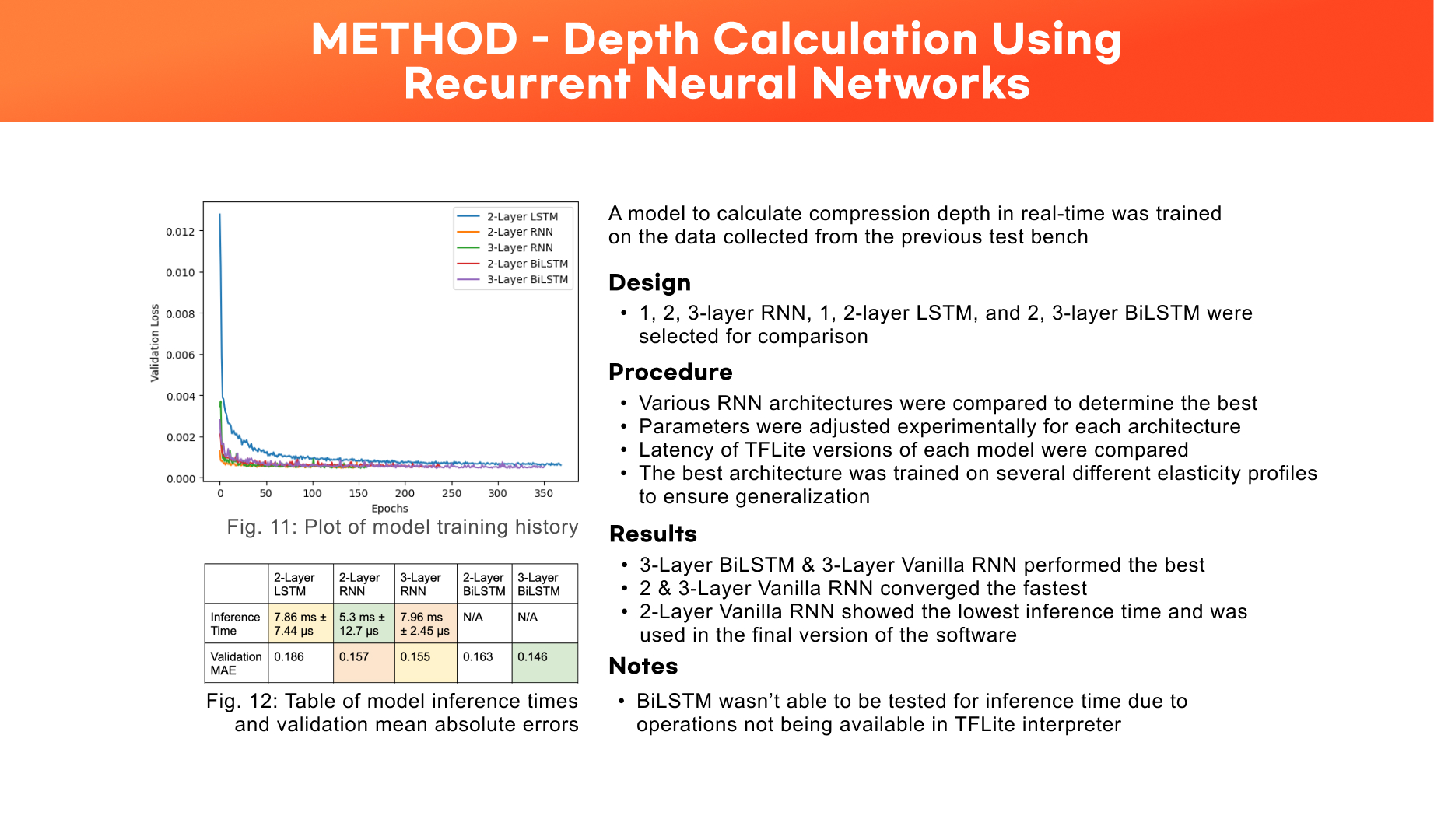

The method I ended up using is basically getting a window of data from both the 9-axis accelerometer and force-sensitive resistor, and then feeding that to a 2-layer RNN or LSTM. They performed pretty similarly but the RNN was faster so I ended up choosing the less powerful model. I collected the data using a custom built testbench (featuring a spring-loaded design) which would record the corresponding depth value with the acceleration and force values in a csv file. The model I trained actually showed a pretty good MAE (of about 0.16 cm), but it didn't work as well once I deployed it. It wasn't horrible, but it also wasn't really up to the ultra-high accuracy I imagined.

I think the main lesson here is that $55 IMUs are just not accurate enough for long-term position tracking. I believe the next step in my project is exploring methods in computational physiology, which is a branch that utilizes mathematical models of physiology to inform inference techniques. Hopefully, I'll be able to do that at research laboratories during undergrad. Anyhow, I hope my short post serves as a guide for anyone who might be attempting similar projects.